The “digital divide” so prominent in public discussion recently is not a new phenomenon after all. In 1999, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), defined the digital divide as one of America’s leading economic and civil rights issues.

During COVID, many aspects of life migrated online: work, school and even essential services. Reliable broadband became vital to a family’s ability to thrive. But the digital divide didn’t disappear once families acquired reliable broadband — a usage gap emerged and that’s proven to be a much tougher issue to solve.

Jen Schradie is a public sociologist and academic researching social media, social class, and social movements — she concludes that a person’s background, education, and income are predictors for whether a person engages in the production of online content, and she says that we aren’t hearing from large sectors of the population (Schradie, 2011). Instead, the stratification that exists in society persists online.

When researchers refer to usage in relation to digital equity, they are interested in whether people have the knowledge required to effectively use technology to produce online content for the public sphere. This takes many forms: creating social media profiles, building websites, posting photos and videos, and writing posts/articles — it also requires a lot of free time.

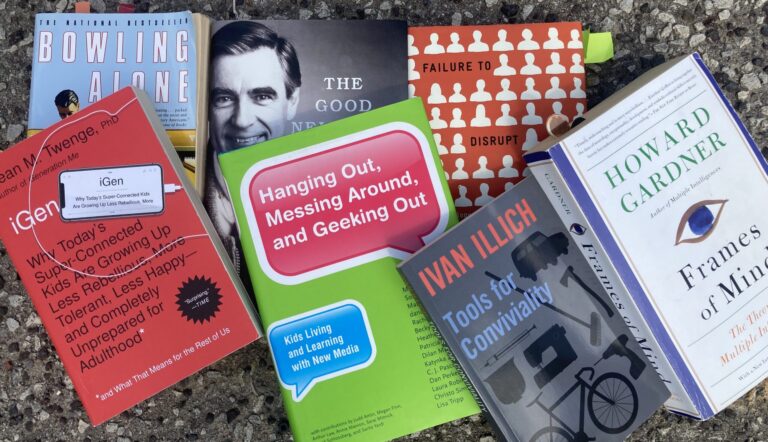

Justin Reich is a Professor in the Teaching Systems Lab at MIT. He also finds that social and cultural barriers are formidable obstacles to equitable participation.

Students from low income & marginalized communities are more likely to use tech for drill and practice and when they use technology, they have limited adult support. Often, their parents and caregivers have limited digital literacy. This is very different from more affluent students: who engage in more creative activities while using tech, and are supported by mentorship from parents, teachers, and adults.

Justin Reich suggests that solutions to the usage issue will emerge outside schools and from within our communities. Solutions will take shape as intergenerational peer-based learning experiences in which children and parents can explore the technology together while engaging in creative activities. This can contribute to “two-gen”, or two generation learning and literacy.

The environment described by Justin Reich exists within community organizations — they are logical places to support children and families progress from online consumers to online creators. The organization’s mentors can help mentees build a playful attitude towards technology, a willingness to succeed, and fail, as well as the confidence to share their work.

According to Mizuko Ito, Professor in Residence at the Humanities Research Institute at the University of California, Irvine, who specializes in new media use amongst young people, the ability to share one’s work is key to creative production. Community organizations just need an online platform where they can deliver programming, connect with children and families and where members can share their creative output.

The importance of having the skills and confidence to produce online content cannot be underestimated. Consuming online content is equivalent to reading, but creating online content is equivalent to writing, and an essential prerequisite to having a voice in the 21st century.

As cities tackle digital equity and the usage gap, they would be well-advised to enlist the help of community organizations with their experienced mentors who have existing relationships with families in the community.

Simply going online does not guarantee anyone a voice.